Last week, I trained a client’s team on crisis management.

It sparked memories of the first crisis I not only witnessed, but certainly exacerbated as a rookie newspaper reporter covering a restaurant’s disastrous opening. I instantly liked the amiable first-time general manager who’d moved his family to the Mississippi riverside town with few dining choices to serve up tasty pancakes, burgers and salads.

The stories I wrote – about labor complaints, food poisoning and a kitchen fire – began with the largely African-American community’s backlash against the franchise’s unfortunate name: Sambo’s. It was the 1,117th franchise. Today, there’s one.

Chris Schroder leading interactive client crisis training seminar at Georgia World Congress Center

As I published numerous articles over the course of a few months, I realized that the restaurant was mired in a series of crises that could have been alleviated with better communication practices.

As I published numerous articles over the course of a few months, I realized that the restaurant was mired in a series of crises that could have been alleviated with better communication practices.

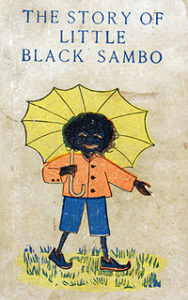

The first issue, of course, was the name of the restaurant: Sambo’s. In 1957, founders Sam Battistone and Newell Bohnett thought they were being clever combining portions of their first and last names to brand their first location in Santa Barbara, California. When diners began associating the new restaurant with an 1899 book – originally meant to tell the story of a heroic dark-skinned South Indian boy who was chased by four tigers, but in more modern times was seen as politically incorrect at best – the owners took advantage, framing and hanging illustrations from the book around the restaurant.

By the time I first walked into the new Mississippi Delta location in 1979 to meet the new GM, the chain had reached its historical peak and had expanded to 1,117 franchises in 48 states. That’s when things started to go downhill. I had never heard of the restaurant before my editor assigned me the story about the new location’s opening, but even I – a recent college graduate working his first professional job – realized it was fraught with peril. After all, we were in the “Queen City” of the Delta and its demographics were 70 percent African-American and 29 percent Caucasian – a reflection of the region’s agricultural plantation era, during which slaves were imported in the 18th and 19th centuries to clear and cultivate rice and cotton farms in the hot, humid environment with spectacularly rich, dark, alluvial soil.

The cover of the original 1899 book, The Story of Little Black Sambo

The restaurant made no effort to clarify or promote the origins of the restaurant’s name before or after it opened, so our readers naturally assumed it was about the book and the pancakes that Little Black Sambo’s mother made from the remnants of the melted tigers. Left to discern their own conclusions, the community decided it was a racist, or at least a racially insensitive, name. Before my arrival in town, the newspaper had published an editorial column from a resident questioning the sanity of a business that would open with that moniker. The small-town conversation was framed and heated discussions were soon to follow. The bottom line was the name was offensive to most of the residents of the region and the owners made no effort to mitigate the issue. Some dropped by to share their views with the management and, if I remember correctly, a few posted signs protesting the business’ presence.

Then, shortly after Sambo’s opened on the main highway, a few diners claimed they were sickened by the food they ate there. As a reporter, that was news, and my editors reported it with headlines in the newspaper that paired the restaurant’s name with those two most unwelcome words: “food poisoning.” Though the restaurant later disputed the claim, it was too late. The brand was set in the community’s collective mind.

Next, employees hired by the new GM claimed they were being mistreated or forced to work hours that were not being fairly or legally compensated according to state labor laws. You guessed it: more negative headlines. While the restaurant had to be measured in its response to a legal matter, the complainants had the freedom to be quoted in my news stories.

The final straw happened one morning when I awoke to the cackle of the police radio, which I kept by my bedside. I was the police and courts reporter, so I responded when there was a lot of unusual chatter on the radio channel. If there was a wreck, plane crash, shooting or, in this case, a fire at the new Sambo’s restaurant, I grabbed my camera and reporter’s notebook, jumped in my car and followed the emergency vehicles to the scene. As it turned out, the Sambo’s fire was due to some electrical problems in the kitchen, but that determination was announced long after the newspaper published the words “fire” and “Sambo’s” in the same headline.

I felt nothing but empathy when the beleaguered GM arrived at the scene of the star-crossed restaurant. His normal good nature had been beaten down, and he and the Sambo’s restaurant itself never recovered. Not only did the Greenville, Mississippi, location close its doors, but so eventually did 1,116 of the other locations. Today, only the original Santa Barbara location is still in operation with the same brand of Sambo’s, and it is owned by a relative of the original co-founder.

The other buildings were sold and many were re-opened by other restaurant franchises. I’ve jumped to the other side, helping businesses leverage positive news and manage or mitigate negative publicity. But many of the principles I preach were developed from watching the dissolution of that quirky California restaurant chain.