My dad wanted his five kids to be lawyers or doctors. “That way, you’ll be a professional, you’ll have a license and you can never be fired by anyone,” he’d remind us as we neared college.

His father was deemed a failed entrepreneur, before failures on an entrepreneur’s journey were as accepted as they are today. My two brothers earned law licenses. My two sisters earned healthcare licenses. I’ve only earned two licenses: for driving and marriage.

I didn’t agree those paths were for me. The career I eventually chose was the one my dad feared most above all others …

… becoming an entrepreneur. It hasn’t always been fun.

… becoming an entrepreneur. It hasn’t always been fun.

These days, successful entrepreneurs love to talk about their failures. Mark Cuban, one of the few billionaires on ABC TV’s hit show Shark Tank, says he’s “been fired from more jobs than most people have had,” adding that each time you fail, it “only makes you better, stronger, smarter.”

That failure narrative, however, is a relatively new one. When my grandfather came of age, in the 1920s, failure was not looked upon kindly – most of all by his wife and father-in-law. My grandfather William, whom I never met, was an ambitious young Atlantan who bought into the Southern Cotton Seed Oil Company in Albany, Georgia and moved his young family – including my toddler father – there in the early 1920s. William’s timing wasn’t good. The boll weevil had begun migrating a hundred miles a year across the South, eventually swarming into south Georgia, wiping out the cotton crop – and his business.

William Schroder, my grandfather, right, with Suzanne Spalding Schroder in 1935, when they were back in Atlanta following two entrepreneurial adventures.

He got up, dusted himself off and moved the family to Miami where he jumped into the hot real estate market where, legend had it, single properties were being sold at auction many times in a one day. The family arrived just in time to witness Florida’s first real estate bubble in 1925. My grandfather figured he’d start anew again. My grandmother, however, a strong woman, had had enough. She insisted the young family move back to Atlanta and live with – and partly off of – her father, a successful Atlanta lawyer named Jack Spalding who had extra bedrooms in his rambling wooden house named Deerland, where Piedmont Hospital sits today.

My grandfather’s role in my family history goes dark about then. By day, he sold lots in a new neighborhood planned off Peachtree called Garden Hills before Wall Street collapsed in 1929. At night, he’d quietly take his place at the formal Deerland dinners – before which my grandmother would say grace, finishing by asking her father and the family to pray for a never-specified “special intention.” My dad later surmised their prayers were for lightning to strike the Albany cotton seed plant, so his dad could collect insurance. It never did.

My father grew up somewhat ashamed of his father’s career, but he worshiped his grandfather Jack (after whom he was was named), a smart, gregarious man who grew up around his own father’s Kentucky legal office before earning his own license to practice law.

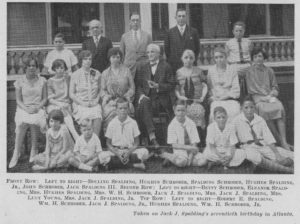

The Spalding family gathered to celebrate Atlanta icon, King & Spalding founder Jack Spalding on his 70th birthday at Deerland. William Schroder is second from left, back row. My father Jack Spalding Schroder is third from left, front row, at his mother’s feet.

When I read Jack’s autobiography recently, I was amused to read of his struggles. He had packed up his new bride and joined a wave of lawyers moving to Atlanta following the success of the first Cotton Exposition in 1881. Jack hung out his own shingle downtown, but his only office visitor that first year was the mailman. Another struggling lawyer in town, Woodrow Wilson, wasn’t succeeding either and moved back to New Jersey (and later to the White House). As Jack had nearly tapped the $1,500 he’d brought to Atlanta, he got his first case – and a break. Henry Grady, then a reporter at the Atlanta Constitution, came by to write a story about Jack’s successful handling of the matter. After the story ran, Jack wrote, he had “never wanted for business since.”

Jack then asked a brilliant lawyer with a photographic memory named Alex King to be his partner. He wrote of them taking turns carrying coal up the stairs to heat their office and running the law firm out of a cash drawer under the front counter. They called the new venture King & Spalding and the firm has prospered to this day.

In his memoir, published in 1926 shortly after my dad’s family had slinked back into Deerland, Jack wrote this sentence with ironic pride: “I have managed to make a living ever since my marriage without any aid to either me or my wife.”

Deerland, the Jack Spalding home on Peachtree, present location of Piedmont Hospital, into which my grandmother steered the family after the collapse of the Florida real estate market.

Jack earned millions of dollars in his day, taking stock options for organizing Georgia Power and huge fees for consolidating railroad companies and advising an emerging Coca-Cola Company and its legion of independent bottlers. He gave away every dollar he earned above a million dollars and asked that his name not be associated with any of his gifts, but many institutions including numerous Atlanta Catholic parishes exist today thanks to his and others’ generosity.

My father earned a license to practice medicine and helped found Emory University Clinic. One of his brothers became a successful lawyer. Dad insisted his children earn a professional license.

I knew I had a creative streak and I would have been a discontented attorney if I had made it through law school. Despite his pressure, when it came time to take my law boards in college, I didn’t set an alarm and purposely overslept. I had found a passion for newspapers in high school and college and eventually worked for six dailies in the South. I was pleased to find I did not need a license. Not long into my career, I couldn’t resist the entrepreneurial fire that burned within me. Twenty three years ago, I quit my job and started a neighborhood newspaper in Virginia-Highland.

To get the first issue out, I needed a bit of working capital. My father – always skeptical of my dream – agreed to lend me $5,000 so I could publish the first issue of Atlanta 30306 (now Atlanta INtown), into which I sold $5,000 in advertising – enough to pay him back. When I drove home from the printer with the first issue, dad called me and urged me to bring him a copy. He sat down and read all 24 pages of the first issue and walked over to me, put his hand around my shoulder and said something I didn’t ever remember him saying in my career: “I’m proud of you.” Two days later, he died.

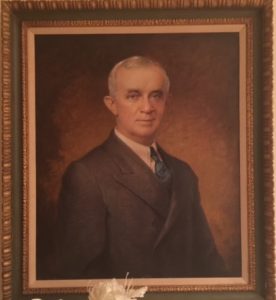

My mother always described William Schroder, my grandfather whom I never met, as a gracious, jovial gentleman who quietly accepted his new role as a diminished figure following his entrepreneurial failures. My family has few photos of him. This portrait hangs in the home of his namesake, Bill Schroder of Vinings.

Sixteen years ago, after the 9-11 terrorist attacks froze the newspaper advertising market, I sold the company, but in all honesty, I turned it over to my business partner, Tom Cousins, who suggested he buy me out or that I buy him out. I had seven years of sweat equity in it. He had invested his dollars three years earlier so we could expand the concept. I turned the keys over to him and left the newspaper business after 23 years of working at six dailies and starting my own neighborhood newspaper chain. Though we had $1.6 million in revenue and 100,000 circulation and 16 employees, it was time for me to go.

At the suggestion of my cousin, Bo Spalding, also a great-grandson of Jack, I opened a public relations firm. I asked Bo if I needed a license to practice PR. He assured me I didn’t.

My firm, Schroder PR, prospered, though we slimmed down during the Great Recession. Today, we employ five full-time employees and some part-timers and we rebranded two years ago to SPR Atlanta as I welcomed a new generation of leadership who may one day buy me out.

At the same time, I took an even bigger gamble investing in a new startup called The 100 Companies, which publishes a weekly eNewsletter, social media platform and website on which this essay appears. I invested my life savings into starting a platform that provides other PR firms an opportunity to publish similar 100-word stories and 100-second videos in their markets.

This startup, like any entrepreneurial venture, is not a sure thing. It takes hard work, late nights, enormous energy and resources – and a stomach of steel to get through the inevitable tough moments all small businesses face in their early years. It is not easy on my wife and family as they watch me gambling what little profits I harvested through the years in the challenged newspaper industry. They fear I may end up broke, broken or out of options like my grandfather.

I, like most entrepreneurs, am an eternal optimist. My architecture friend, Norris Broyles, calls me the Energizer Bunny – “you get up and keep going after facing adverse circumstances in your personal and professional life.”

I trust and thank God for my family and friends, for business opportunities and for what good fortune I’ve experienced and what little fortune I may have earned and now gamble again. I look to my grandfather and try to maintain grace under pressure in the face of potential failure or success. I look to the confidence in me that my mother always expressed each time I visited her until the day she died last March at age 99.

And each morning, I leave my house and look up at a formal portrait of my great-grandfather Jack Spalding and his ever-watchful gaze before I head into the office to lead my two entrepreneurial enterprises. I give Jack a little nod as I leave – smiling – knowing that, one day, even he may be proud of me too.

12 comments

Chris,

I really enjoyed reading your story today! I love your transparency !

It was interesting to read about your family in Atlanta since I grew up here as well and had relatives in Albany and middle Ga.

You are an inspiration to all entrepreneurs I am sure!

I always enjoy reading the stories in the Atlanta 100 also!

Keep up the good work!

Karen smith Hall

Leadership ministries inc. Atlanta, ga

Great story! Chris has been my friend for many years, and suffers from the same “serial entrepreneurism” as i, and as always, i wish him and the atlanta 100 great success. it has been said it’s not the destination, but the journey that matters, and in the time i’ve known him, chris, with the tremendous support of his charming wife, jan he has managed the journey with particular style.

My third COUSIn, who has succeeded through his own mettle. Congrats, cuz!

Charlie Spalding

Well, you understand.

Chris –

Great piece! You speak for all entrepreneurs.

Eric

A wonderful personal story, and the grandfather (“Father” to his sons) in you is now experiencing in you the entrepreneurial success that eluded him but that he richly deserved due to his own success as a person. For that success I am proud to have his portrait in my home and, yes, I smile up at him every single morning and revere his personal qualities. Thanks

I love this, Chris!!! Shared it with all my kids!!!

Especially loved the story of your dad sharing his love and encouragement with you before he passed away❤️.

May the story continue…..

Chris, a comment from perhaps your most senior reader. Congratulations. I am very proud of you and glad you are a dear frienD to many EGANS.

enjoyed the story! Oscar wilde summed it up for us, “we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars” the entrepreneur!

Cheers to shooting for the stars

Chris,

Enjoyed reading about your family history and admire your passion and entrepreneurship. I live with an entrepreneur and recognize all the endless work and sacrifices they make for their beliefs. Congrats to making your dreams come true!

Chris,

Cheers to your resolve and insight to have made me think and enjoy and learn through your words. The “Chris Wit” and sensitivity would have landed you nowhere else than where you are.

You write beautifully and I loved reading your story. I was terrified of

Grandmother schroder. She said i was so bad that satin was going to burn me in hell. Poor Mr. Schroder. Nobody remembers him because your geandmother was so “strong.” Finally, your uncly billy, my father, use to to to tell us thqt you and you sibblings were “wierd,” “differeNt” because your father had married his 16th cousin. Well, i just think you are swell.

[…] one thing he insisted was that I’d never become an entrepreneur. Imagine his horror if he knew I launched an agency where clients could hire and fire you […]